Sanjo district in the Middle Ages

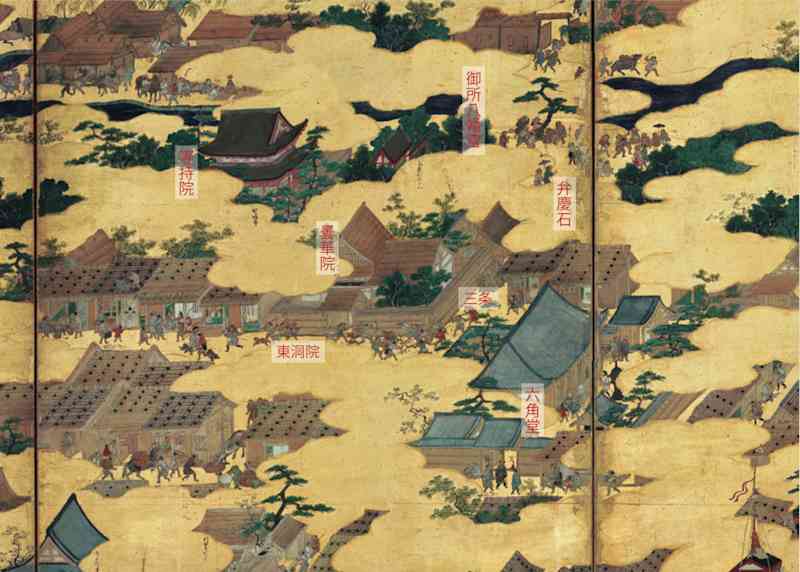

Sanjo Dori on the right part of the Folding Screen of Uesugi Hon Rakuchu Rakugai Zu, Source: Yonezawa City Uesugi Museum

After the advent of the Kamakura shogunate at the end of the 12th century, Kyoto and its important Sanjo Dori continued to maintain its role as a political and cultural center.

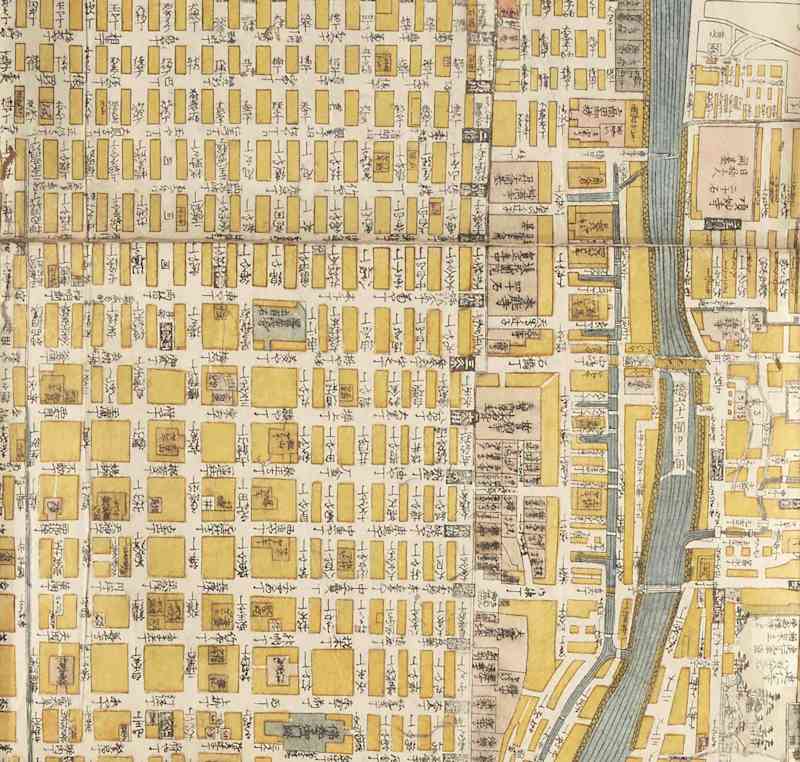

Although many details about the area around Sanjo Avenue during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) are not known, it is certain that it was a busy street lined with aristocratic residences, homes of commoners, and inns of samurai warriors.

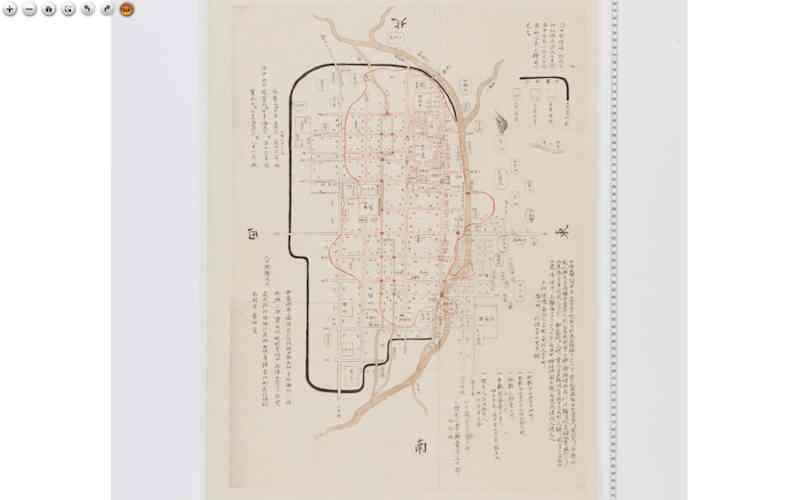

After the fall of the Kamakura shogunate in the mid-13th century and the upheavals of the Northern and Southern Dynasties following the new Kenmu Restoration, a new warrior government, the Ashikaga shogunate, was established. This shogunate is usually referred to as the "Muromachi Shogunate," and the shogun's palace in the early days was located in Sanjo, Shimogyo. In particular, during the reign of Takauji Ashikaga, a residence for him was established in Sanjo Bomon Alley, which later became known as Tojiji.

Even after the shogunate was moved to Kamigyo during the reign of Yoshimitsu, the Sanjo area of Shimogyo retained its historical importance, and the 4th Shogun Yoshimochi and the 10th Shogun Yoshitane established their shogunal residences here. The residences of feudal lords and warriors were concentrated in this area, and Sanjo Dori continued to function as part of the political center of Kyoto.

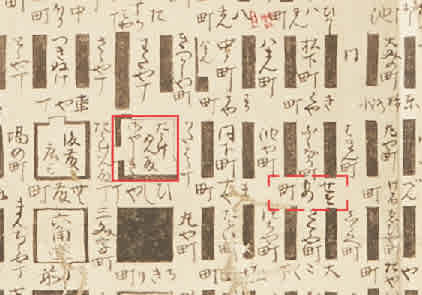

The "Uesugi Hon Rakuchu Rakugai Zu”, which was painted in the Sengoku Period, depicts in detail what Kyoto was like at that time, and shows that Kamigyo and Shimogyo were independent areas surrounded by walls and moats called “Sogamae” respectively. Sanjo Dori is an important road that crosses the northern part of Shimogyo from east to west, and the "Uesugi Hon Rakuchu Rakugai Zu" depicts the residence of Zuichiku Takeda on the north side of Sanjo Dori, between Karasuma Dori and Muromachi Dori. Zuichiku was a first-rate doctor of his time, and people lined up at his door waiting to see him.

In addition, a temple is depicted to the northeast of the intersection of Sanjo Dori and Higashinotoin Dori, which was known as the nun-monastery of Tsugenji, which was opened in the early Muromachi period. Since Donge-in, a pagoda temple of Tsugenji, became famous, the entire temple came to be known by that name.The Dongein, depicted on the folding screen, has a wood-board roof in the style of an aristocratic residence instead of tiles, creating a soft atmosphere typical of a nunnery.